FASTQ from First Principles

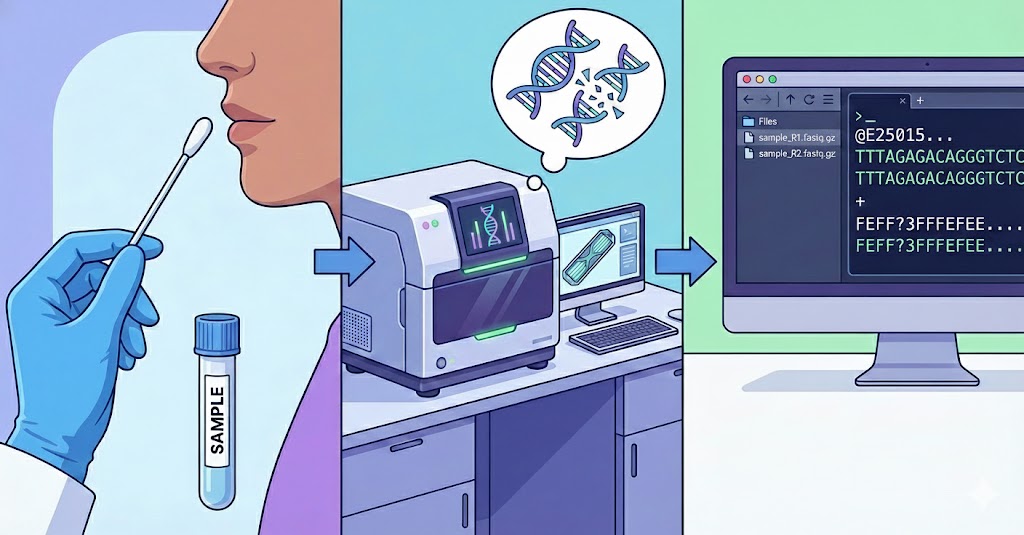

I recently had Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) performed on my DNA. I swabbed the inside of each of my cheeks with a nylon swab, placed each swab in a collection tube, and mailed those collection tubes off to a lab. A few weeks later, I received four files from the lab:

- sample_R1.fastq.gz - 35.76 GB

- sample_R2.fastq.gz - 38.73 GB

- sample.bam - 71.26 GB

- sample.vcf.gz - 426.8 MB

Ignoring the gzip extensions, the files consist of two FASTQs, one BAM, and one VCF. I wanted to understand what these files actually represent rather than treat them as opaque pipeline inputs. This post focuses on the two FASTQs. But first, a brief detour into the process of DNA sequencing.

A Brief Overview of Shotgun Sequencing

Recall from high school biology that the human genome is encoded in Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), a molecule composed of two strands. Each strand consists of individual nucleotides—Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G)—chained together. The two strands of DNA are complementary, with A pairing to T and C to G. Each pairing is known as a base pair (bp). Most humans have approximately 6.2 billion of these base pairs in the nucleus of each cell in their body, divided amongst 23 pairs of chromosomes1. Generally, most2 cells in the human body will contain roughly the same 6.2 billion base pairs of nuclear DNA.

My cheek swabs that arrived at the lab likely contained on the order of several hundred thousand to millions of my cells3, each containing a copy of my genome. The lab broke open these cells and extracted long strands of DNA. It then intentionally broke those strands into small fragments a few hundred bp in length, hence the term shotgun sequencing. Onto each end of these fragments, the lab attached a short sequence of synthetic DNA. To reduce costs, labs will typically sequence many samples at once, so the adapters include a unique ‘barcode’ (index) to identify which fragments belong to which sample. This is known as multiplexing. At this point, the lab had many fragments of my DNA that looked like this:

[Adapter A]-[My DNA insert, a few hundred bp]-[Adapter B]The lab loaded these fragments onto the sequencer. Then, for each fragment, the sequencer sequenced 150 bp4 in from each end, one nucleotide at a time—a process that took on the order of one to two days. Each of these 150 bp sequences is known as a “read”. Because the sequencer sequences from both ends, each fragment produces two reads: one read starting from adapter A and one starting from adapter B. These two types of reads correspond to the R1 and R2 FASTQ files I received from the lab. One common target for labs is to break fragments into a roughly 300 bp insert size. If the insert is exactly 300 bp, the two reads will cover the insert perfectly. If the insert is larger, base pairs in the middle will not be covered by this read pair; if the insert is shorter, the two reads overlap.

Onto the FASTQ

FASTQ files are beautiful in their simplicity. They are simply text files, where each read from the sequencer constitutes 4 lines of the file. Grabbing the first read out of the file is as simple as:

zcat sample_R1.fastq.gz | head -n 4

@E250152413L1C001R00100000622/1

TTTAGAGACAGGGTCTCAGTGTGCCGCCCAGGCTAGACTGCAGTGGTGCAATCATAGCTCACTGAAGCCTTGAACTCCGGGGCTCAAGTGATCCTCCTGCTTCAGTCTCCAGAGTAGCTAGGACTACAGGCACGTATCACCATGGCTGGC

+

FEFF?3FFFEFEEFFFFFFDFEFFFFFFFFFFFF@F<FFFFFDFFFFFBFFFFBFFFFFFEFFF=FFFEFFFDDFFFFEEEFFFFFCFFFDFFFFFFFFDFFF;@FFFFFFF<FFFEDFFFFFECFFFD=FFFFFEFF8EFFFFEEFFDFYou’ll notice that zcat was used in place of cat as the file is compressed. If the file were uncompressed, cat could be used. When on macOS, you may need to use gzcat.

Now, let’s break down those lines:

- The first line,

@E25015..., is an identifier line containing metadata about the read. The format of this line will vary based on the manufacturer of the sequencer (in this case, MGI). - The second line,

TTTAGA..., is the sequence of nucleotides recorded by the machine for this read. You’ll notice it is exactly 150 characters in length5. Although this specific read does not, some reads may contain the character N, meaning the sequencer couldn’t confidently determine the base at that position. - The third line,

+, is simply a separator. - The fourth line,

FEFF?3..., is the sequence of ASCII-encoded Phred+33 quality scores corresponding to each nucleotide above. There will be more on this below, but for now just observe that it is the same length as the nucleotide sequence above.

Next, let’s find the total number of reads in each of my FASTQ files:

zcat sample_R1.fastq.gz | wc -l | awk '{print $1/4}'

367510679

zcat sample_R2.fastq.gz | wc -l | awk '{print $1/4}'

367510679As expected, the number of reads in each file matches; each fragment was read from both ends. For reasons that will be discussed in later posts, the clinical standard is to have, on average, 30 reads at each base pair on the genome. This is commonly referred to as “30x depth” or “30x coverage”. Between R1 and R2, I have 367,510,679 + 367,510,679 = 735,021,358 total reads. If each of these is 150 bp in length, that’s 735,021,358 * 150 = 110,253,203,700 total bases. Divided by the ~3.1 billion bp per set of chromosomes6, that’s 110,253,203,700 / 3,100,000,000 = 35.57 average reads per base. Note that this is a rough approximation of depth. A real clinical WGS would include some quality control filtering.

What is Phred+33?

Each base in each read in the FASTQ file has a corresponding “Phred quality score” (Q). The Phred quality score gives the probability (p) that the corresponding base call is wrong via the following equation:

So a Phred score of 0 means that the probability of error is 1.0 while a Phred score of 40 corresponds to an error probability of 0.0001. In a FASTQ, Phred quality scores are represented by a character, not a number. This character is the ASCII representation of the Phred score plus 33. For example, a Phred score of 0 corresponds to a Phred+33 of 33, which is a ! in ASCII. 33 was chosen as an offset because ASCII 33 (!) is the first readable character. Characters before 33 are control characters or whitespace that do not render well in a terminal or text editor. Labs generally cap Phred scores at ~41, which corresponds to 41 + 33 = 74, or the ASCII character J.

The first six bases from my first R1 read are TTTAGA with corresponding Phred+33 characters FEFF?3. This gives the following probabilities that each base is incorrect:

| Base | Phred+33 Char | ASCII Value | Phred Score (Q) | Error Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | F | 70 | 37 | 0.02% |

| T | E | 69 | 36 | 0.025% |

| T | F | 70 | 37 | 0.02% |

| A | F | 70 | 37 | 0.02% |

| G | ? | 63 | 30 | 0.1% |

| A | 3 | 51 | 18 | 1.58% |

Conclusion

You may now be wondering how any of this is useful. I have, across my two FASTQs, ~735 million reads and corresponding quality scores for each read, a huge amount of data. But how do I know where on my genome each read is actually from? Given that first read, how do I know if it is from chromosome 2 or chromosome 22 or even from mitochondrial DNA? How do I then, from there, determine my APOE status or my ancestry?

At this point, there are two paths forward: one can either “assemble” the reads—mathematically put them back into a single sequence based on overlap between the reads—or “align” the reads—match each read to an already assembled “reference genome”. Because assembly is very computationally expensive, the common path forward is alignment. Aligning the FASTQs to a reference generates a Binary Alignment Map or BAM file. BAM files will be discussed in the next post.

Footnotes

-

Each cell also contains many mitochondria. Each mitochondrion contains multiple copies of its own ~16,500 bp genome. This mitochondrial DNA will appear in WGS results. ↩

-

Red blood cells have no nucleus, gametes (sex cells) are haploid (contain one set of chromosomes), and some human cells are polyploid (contain multiple sets of chromosomes). But the vast majority of human cells are diploid (contain two sets of chromosomes). ↩

-

The sample will also contain detritus and various microbes with their own DNA. The sequencing process can read some of that material too, so the FASTQs may include a small fraction of non-human reads. This will be relevant in later posts. ↩

-

Technically, these are 150 bases, not base pairs, as reads are derived from a single strand, but people commonly still write “bp” as a unit of read length. ↩

-

The FASTQ files received from the lab are typically already demultiplexed, with the synthetic DNA of the adapters removed, so these 150 bases are intended to be from the insert. ↩

-

Depth is calculated against the haploid (23 chromosome) base pair count, not the diploid (46 chromosome) base pair count for reasons that will become apparent in later posts. ↩